Flux 简介

目录

Flux 基本概念

Flux 是 InfluxDB 2.0 的原生语言。Flux 用于

- 编写查询以检索数据。

- 根据需要转换和调整数据。

- 与其他数据源集成。

Flux 是一种专为使用 InfluxDB 数据格式而设计的函数式语言。为了最大限度地发挥 Flux 的作用,了解底层的 InfluxDB 数据模型及其与 Schema 的关系非常有用,因此请务必阅读并理解上面关于设计 Schema 的部分。

在上一节中,您接触到了“足够用的” Flux,但是有一些重要的 Flux 概念需要理解。

Flux 是一种函数式语言

Flux 从根本上来说是一种函数式语言。您编写的大多数 Flux 代码本质上都是在创建和链接函数。函数可以显式命名,或者通常是匿名的,这意味着您可以在不命名的情况下内联声明函数。

之前,我们介绍了 filter。

|> filter(fn: (r) => r._measurement == "measurement1")

filter() 是一个函数,它本身接受一个函数作为参数。然而,最常见的是,filter 的函数是内联定义并匿名提供的。或者,您可以命名 filter 并使用 filter 名称

afilter_function = (r) => r._measurement == "measurement1"

from(bucket: "bucket1")

|> filter(fn: afilter_function)

我们可以进一步研究函数 afilter_function 并对其组件进行更详细的分析。

因为 Flux 是一种函数式语言,所以函数是一级对象。因此,第一步是指定标识符(“afilter_function”)和赋值运算符(“=”)。下一部分是参数列表,在本例中是一个简单的“r”,代表行。后面跟着 lambda 运算符(“=>”)。最后是函数体本身。

afilter_function = (r) => r._measurement == "measurement1"

函数体可以是多行的,其语法处理如下

afilter_function = (r) => r._measurement == "measurement1"

and r._field == "field1"

声明式

Flux 是一种声明式语言。这意味着您的 Flux 代码是为了实现代码中表达的目标而执行的,而不一定是按照您指定的特定方式执行的。这归结为 Flux 执行引擎应用规划器来优化您指定的运算顺序,以实现更好的性能。您将始终获得您要求的结果,但 Flux 实现这些结果的方式可能与您指定的特定方式略有不同。

这将在 Flux 优化部分进行更深入的介绍。

Flux 是强类型和静态类型的

Flux 语言是强类型的。然而,类型是隐式的。虽然您不需要声明对象的类型,但在程序运行时会推断类型,并且类型不匹配会导致错误。

此外,您无法在运行时更改 Flux 中对象的类型。对象的类型是不可变的。

Flux 对象是不可变的

对象的值也是不可变的。例如

astring = "hi"

astring = "bye"

会导致错误

@2:1-2:18: variable "astring" reassigned

请注意,表中的数据不是不可变的。这将在关于转换数据的章节中详细介绍。

Flux 参数是命名的

除了通过管道转发运算符传递的表之外,所有 Flux 参数都是命名的。这使得您的 Flux 代码更具自文档性,同时也允许对 Flux 语言进行更多非破坏性更改。

Flux 参数类型可以重载

在许多情况下,单个参数可以接受多种类型的参数。在下一节的 range() 部分 中将对此进行详细介绍。

管道转发

Flux 旨在通过在函数之间传输数据来转换数据,每个函数依次转换数据。此运算符是管道转发运算符“|>”。

因此,您可以看到以下代码以 from() 开始,然后将 from 的结果通过管道转发到 range()。

from(bucket: "bucket1")

|> range(start: -5m)

然后可以将其通过管道转发到更多函数,例如 filter()

from(bucket: "bucket1")

|> range(start: -5m)

|> filter(fn: (r) => r._measurement == "measurement1")

如上所述,函数体由一组参数、lambda 运算符和函数运算定义。此外,在调用函数时,所有参数都是必需的命名参数。然而,管道转发有一个在函数之间传递的隐式参数,即由前一个函数修改的表流。

可以在管道转发运算符右侧的函数在其参数列表中使用特殊名称“管道接收字面量”来声明这一点。

(tables=<-)

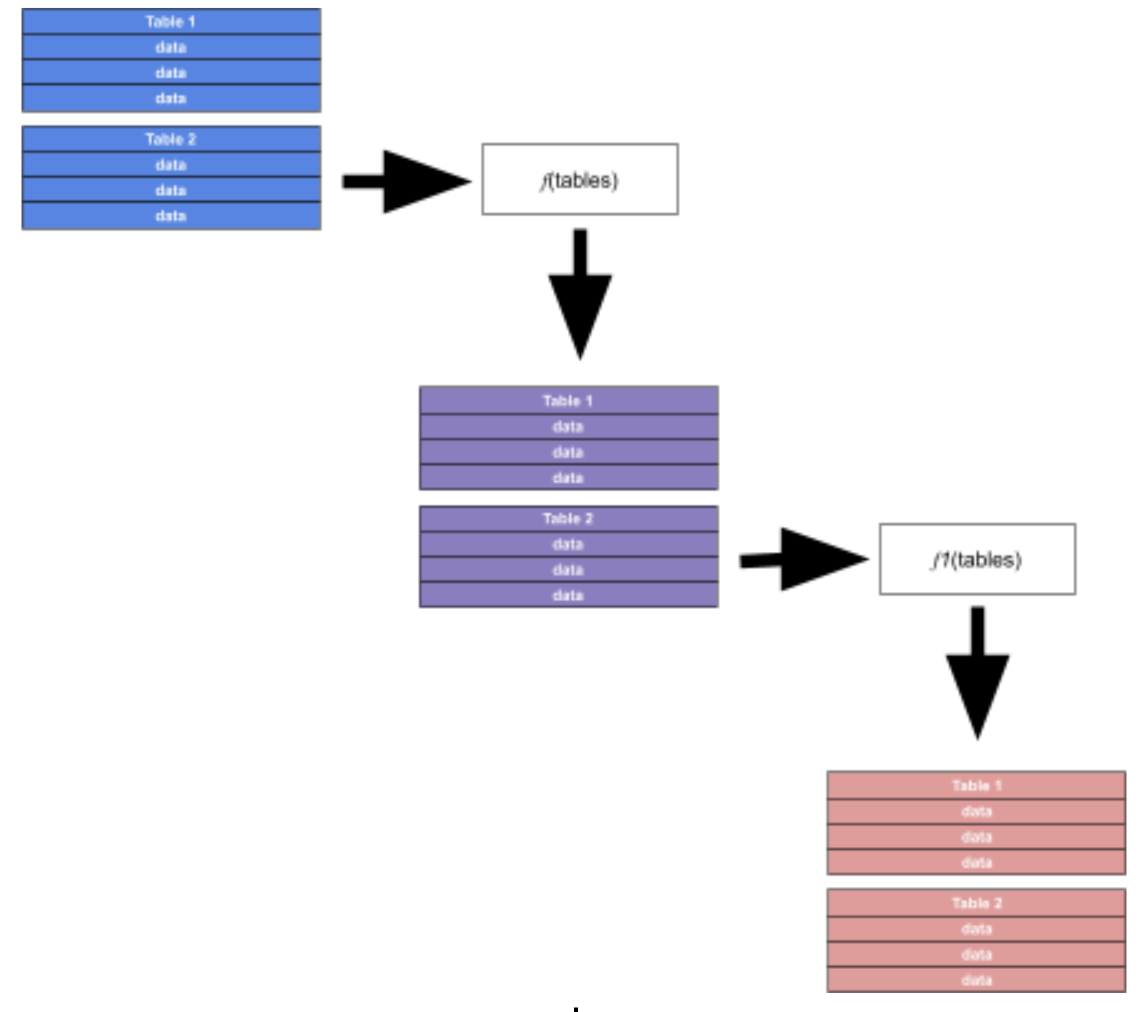

因此,接受管道转发数据的函数体如下所示

functionName = (tables=<-) => tables |> functionOperations

一个实际的例子是一组常用过滤器的应用

afilter_function = (tables=<-) =>

filter(fn: (r) => r._measurement == "measurement1")

filter(fn: (r) => r._field == "field1")

filter(fn: (r) => r._value > 80.0)

from(bucket: "bucketa")

|> range(start: -5m)

|> afilter_function()

Flux 对表的流进行操作

管道转发运算符的结果是 Flux 函数对应用于它们的每个表的每一行进行操作。回顾一下,当您将数据写入 InfluxDB 时,数据会写入存储引擎中的单独表中,每个表都具有唯一的测量值、标签值组合和字段组合。当您查询这些数据时,这些表会被读取并流式传输到 Flux,然后每个表的每一行都会通过每个函数。

您不能要求 Flux 对一个表进行操作而不对其他表进行操作。您也不能要求 Flux 对一行进行操作而不对其他行进行操作。每个表中的每一行都将进行相同的转换。

Flux 支持使用 Map 语义进行循环

传统语言支持使用 for 循环等循环结构。Flux 使用 map() 通过将函数应用于流中每个表的每一行来实现其他语言中循环的目的。

点符号 vs. 括号符号

因为 Flux 借鉴了 javascript,所以 Flux 支持点符号和括号符号来访问成员。以下两行是等效的。

filter(fn: (r) => r._measurement == "measurement1")

filter(fn: (r) => r["_measurement"] == "measurement1")

没有正式的约定来确定使用哪种符号,两者都是有效的。然而,生成的代码通常使用括号符号,因为如果生成的代码基于用户提供的数据,则数据本身中可能包含会导致语法错误的字符。例如,如果我生成一个包含句点的标签,例如 sensor.001,则使用点符号的生成代码将被破坏

filter(fn: (r) => r.sensor.001 == "astring")

vs.

filter(fn: (r) => r["sensor.001"] == "astring")

第一行将是语法错误,因此代码生成器通常会生成第二行。

包

Flux 附带了一个大型函数库。这些函数被组织成 包,统称为 stdlib。

内置函数

stdlib 附带了一组“内置函数”,这意味着您无需导入即可使用它们。这些是最常用的函数,到目前为止介绍的所有函数(from()、range() 和 filter())都是内置函数。

导入

其他包设计用于更具体的领域,并且必须导入才能使用。因此,例如,如果您想在 Flux 函数中使用 CSV,则需要导入 csv 包,如下所示

import "csv"

之后,可以使用点符号访问 csv 包中的函数

csv.from(csv: csvData, mode: "raw")

也支持括号符号,您可能偶尔会看到

csv["from"](csv: csvData, mode: "raw")

以下是导入 csv 包并从中调用函数的最小示例

import "csv"

csvData = "value,key\n1,a"

csv.from(csv: csvData, mode: "raw")

|> yield()